My intercom - Part 1

Introduction

In this day and age, a surprising amount of devices can be hooked to the internet. My door intercom for example can be connected to the Wi-Fi. This feature naturally piqued my interest, namely: can I unlock the two central doors from my apartment building from my laptop or any other device? Or can I snoop using the installed cameras?

You would think that there would be software for this already, but considering most intercom systems use a mix of proprietary software and unrecognizable protocols, this seems to be partially the case. What follows in a series of articles is a project which is probably going to cost me months, all because: “I don’t like the interface of my intercom”.

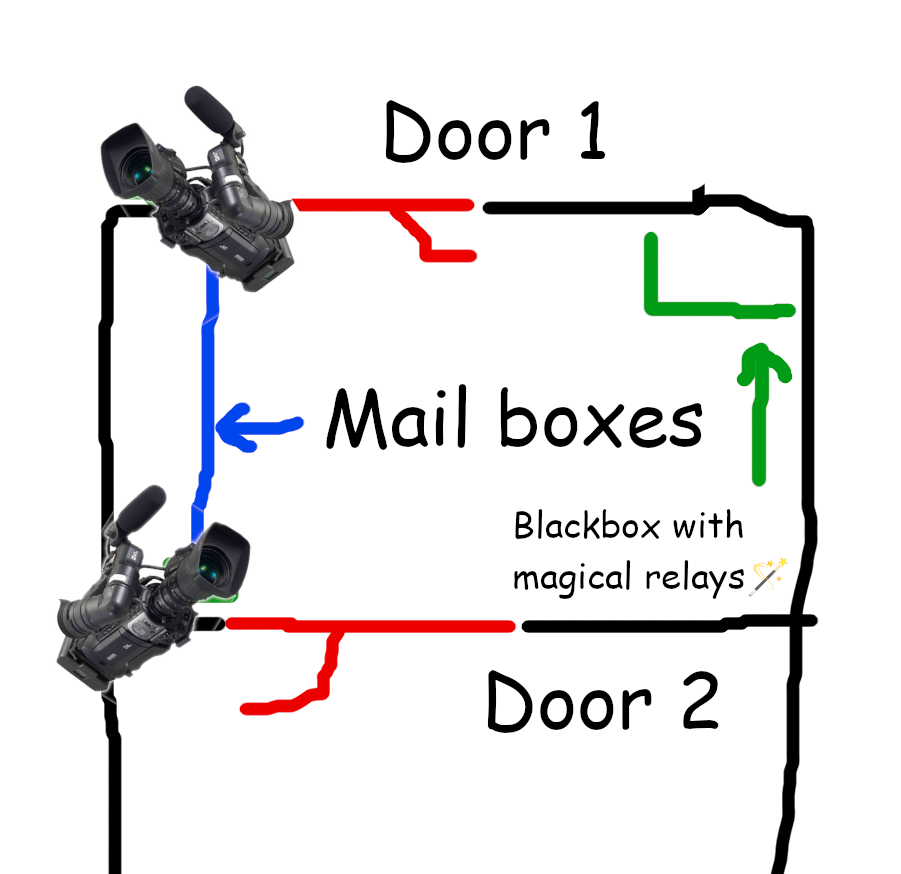

To give some context on my apartment and the use of the intercom: the intercom can open two doors, and look at two cameras. The first door is a door from the outside world to the inside of the building (“Door 1”). It’s used by f.e. the mailman to be able to enter an area for the mailboxes. That door is always open from early morning to somewhere in the evening, and can actually be pushed open (which not everybody knows). However, it can also be opened by the intercom. The second door from the “mailbox area” to the rest of the building (“Door 2”) is always closed, and to open that door, somebody needs to ring the intercom after which I need to push some buttons on my intercom (or naturally you can open it if you have a key).

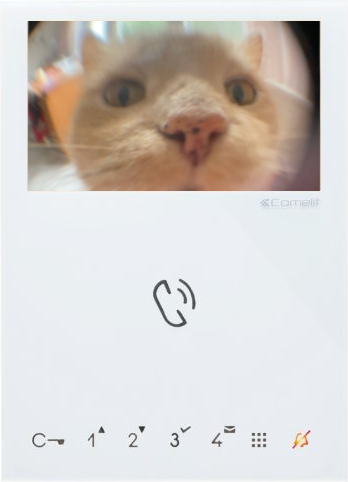

The problem here are the buttons. The buttons are these horrible partially responsive pieces of garbage. When you touch them, there’s this unnatural long delay and then a magic coin flip to decide if you actually touched it or not. So, why can’t I open the doorbell from any other device, so I won’t have to use the buttons anymore ….

My intercom is from a brand called Comelit, an Italian surveillance company [1], and the type is “Mini Wi-Fi” [2]. Out of the box, Comelit has a range of apps in the Google Play Store you can install. With these apps you can connect with your doorbell and open the door from your phone. Now, I could stop right here, and call it a day, because essentially the Android app allows me to open the door; button problem fixed! However, the app also sucks.

The main “Comelit” app is the one I’ve installed in the past and for the sake of these articles. It’s a pretty terrible app from the users’ point of view. F.e. after you set it up, it needs location access, which is only required because of tracking (Comelit is after all a surveillance company). Another bad example is that the intercom doesn’t always show up in the app, even after somebody ringed my intercom. And above all, it’s very sluggish in detecting that somebody is actually at the door (more on that later).

Connecting to my router

The first step to see if I can open my door with my laptop, is connecting my Comelit Mini Wi-Fi to the actual Wi-Fi. This is where the pain begins. There’s no touchscreen on the doorbell so you have to navigate an on-screen keyboard using these horrible partially responsive touch-only buttons (the torture). After typing in my Wi-Fi password, it connects! Checking my router I see it pop-up as DEV-18:3A:98 with the following internal IP 192.168.1.9. After ten to twenty seconds it dissappears from the router, which initially confused me. However, the reason for that is that after the intercom is idle for a while, the doorbell will turn itself off and disconnect from the router.

And yes, this means that for whatever test I want to do, I need to physically move to the intercom, tap one of the buttons, let it connect, and then run the test.

What runs on my intercom?

Knowing that it is possible to control the doorbell through the Comelit Android app there must be a server of sorts running on my intercom. To figure out what that is I use nmap, a pretty standard port scanner. First I run:

nmap -Pn 192.168.1.9

Which returns me the following details:

Starting Nmap 7.93 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2023-01-10 15:45 CET

Nmap scan report for 192.168.1.9

Host is up (0.000019s latency).

All 1000 scanned ports on 192.168.1.9 are in ignored states.

Not shown: 1000 filtered tcp ports (no-response)

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 15.22 seconds

This response means that not a single one of the top 1000 ports is opened. This asks for a brute-force nmap:

nmap -p 1-65535 192.168.1.9

This returns a bit more information:

Starting Nmap 7.93 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2023-01-10 15:50 CET

Nmap scan report for 192.168.1.9

Host is up (0.0057s latency).

Not shown: 65380 closed tcp ports (conn-refused), 151 filtered tcp ports (no-response)

PORT STATE SERVICE

53/tcp open domain

8080/tcp open http-proxy

8443/tcp open https-alt

64100/tcp open unknown

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 134.15 seconds

Success!

HTTP-ports 8080 and 8443

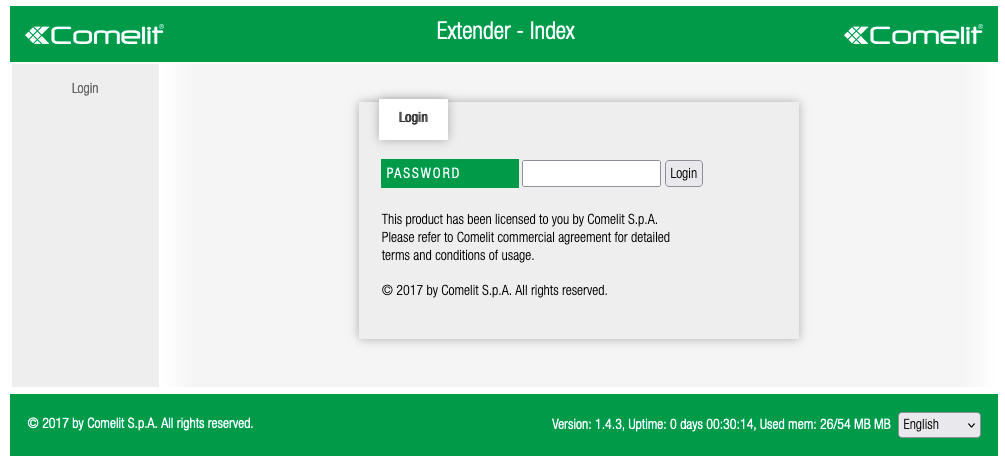

Ports 8080 and 8443 are browsable from the internet. When browsing port 8080 I’m being hit with a page which requires a password, a page with the name “Extender - Index”. It looks like this:

It’s nice to know my intercom has memory, and it apparently uses about half of its 54 MB. If I go to the 8443 page I’m being hit with a bad SSL certificate error, if I decide to trust it anyway I’m being pretty much redirected to the same page that lives on the 8080 port. Why does it have a https-alt without an SSL certificate? I’m assuming the SSL certificate is only valid for the internal domain that is resolved by the domain server on port 53.

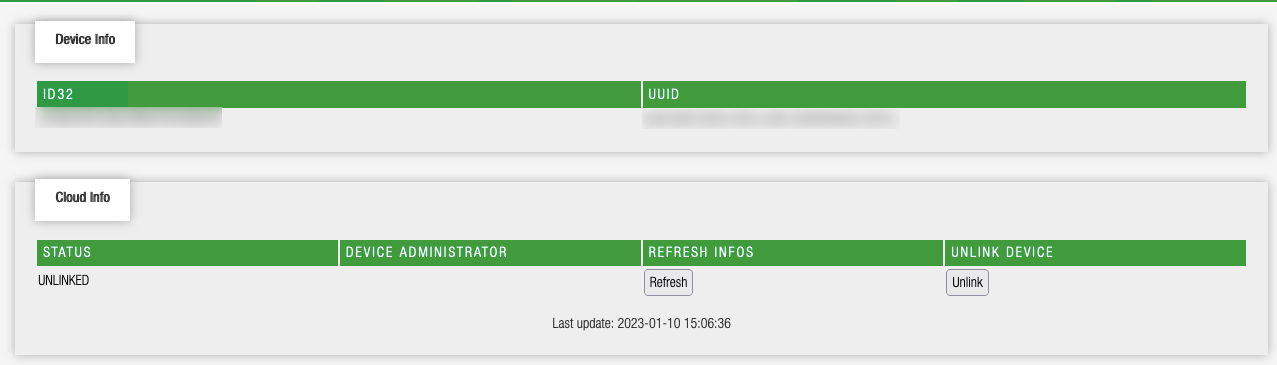

After some Googling I find out that the password to fill in at the “Extender index” screen is simply admin, and with that I gain access to my intercom. It doesn’t give me much, just options to reboot my intercom, change the password on my intercom and some device info. The device info page is the most interesting. It has two tables:

One table is called “Device info” and has two identifiers, which I both blurred out. One is a UUID and the other a 32-byte string; I’ll trust that it is actually 32 characters long. The Cloud info is the most interesting table here. It says that I have a device that is “UNLINKED”, which I can then “Unlink”; confusing.

Port 64100

Checking the nmap scan, there’s one other port that’s left, which is port 64100. Could that be the port the Comelit Android app actually uses? To confirm this, I installed an Android app called “PCAPDroid” (it’s essentially Wireshark for Android) [3] to see what requests Comelit actually makes from the app to open the door, and perhaps see images from the camera and what not. Alongside that I tried to reverse engineer the Comelit APK through various tooling [4], and all in all this is what I found out:

- The Android app uses port 64100.

- The intercom allows a mix of TCP/UDP requests

- The intercom uses some sort of JSON API mixed with other magic

Initally I thought whatever lives on that port would speak HTTP, so in order to naively repeat a request to my intercom I did:

curl --data '{BLURB OF JSON I TOOK FROM PCAPDroid}'

http://192.168.1.9:61400

And it returned me this:

curl: (1) Received HTTP/0.9 when not allowed

This means that whatever lives on port 61400 doesn’t speak http version 1.0 or later. I can use the --http0.9 flag and get a response, but it just returns a blurb of unreadable bytes. I turn back to the logs I received from “PCAPDroid”, and in there I inspect some of the JSON responses (partially redacted, and formatted). For example:

<8 partially readable bytes>

{

"message":"get-configuration",

"message-type":"response",

"message-id":2,

"response-code":200,

"response-string":"OK",

"viper-server":{

"local-address":"192.168.1.9",

"local-tcp-port":64100,

"local-udp-port":64100,

"remote-address":"",

"remote-tcp-port":64100,

"remote-udp-port":64100

},

"viper-client":{

"description":"XXXX"

},

"viper-p2p":{

"mqtt":{

"role":"a",

"base":"XXXX",

"server":"tls://hub-vc-vip.cloud.comelitgroup.com:443",

"auth":{

"method":["CCS_TOKEN","CCS_DEVICE"]

}

},

"http":{

"role":"a",

"duuid":"XXXX"

},

"stun":{

"server":[

"turn-1-de.cloud.comelitgroup.com:3478",

"turn-1-de.cloud.comelitgroup.com:3478"

]

}

},

"sbc":{

"pm-always-on":false

},

"vip":{

"enabled":true,

"apt-address":"SB000006",

"apt-subaddress":2,

"logical-subaddress":2,

"apt-config":{

"description":"",

"call-divert-busy-en":false,

"call-divert-address":"",

"virtual-key-enabled":false

}

},

"building-config":{

"description":"yourbuilding"

}

}

If I look up some of the terms in this JSON blob on the internet, I find a lot of interesting things. The first thing that I look for is “viper-server”, which returns nothing of interest. If I extend the search to “viper-server Comelit”, I kid you not, the first hit is an IP address of somebody’s actual doorbell, followed by a technical manual from Comelit (funny), followed by three more doorbells that are accessible from the internet.

Obviously, I try to see if the default admin password works for the four doorbells in question, and it fortunately doesn’t. It’s still pretty awful that these doorbells are accessible from the internet and indexed by Google, because an IP address can very easily be converted to a physical location. Perhaps, in a follow-up to this article I might try and see if the ports 64100 are open as well for these doorbells.

The next keyword is the viper-p2p entry, which contains quite a bit of information. It mentions a thing called a stun server [5], which is a term I’m familiar with because I recently experimented with WebRTC in relation to file transferring. Looking for viper-p2p also didn’t give me much, and was a dead-end. The next thing I see is mqtt which is something I have no clue about, but it’s a messaging protocol for IoT devices, so it seems, which my intercom is of course. The server is located elsewhere on the planet, and is controlled by Google, which is something I found out by doing a simple ping to the server that is listed:

ping hub-vc-vip.cloud.comelitgroup.com -p 443

PING hub-vc-vip.cloud.comelitgroup.com (34.77.55.26) 56(84) bytes of data.

64 bytes from 26.55.77.34.bc.googleusercontent.com (34.77.55.26): icmp_seq=1 ttl=105 time=18.9 ms

64 bytes from 26.55.77.34.bc.googleusercontent.com (34.77.55.26): icmp_seq=2 ttl=105 time=17.5 ms

Pinging one of the STUN servers results in:

PING turn-1-de.cloud.comelitgroup.com (45.77.52.30) 56(84) bytes of data.

64 bytes from 45.77.52.30.vultrusercontent.com (45.77.52.30): icmp_seq=1 ttl=50 time=18.5 ms

64 bytes from 45.77.52.30.vultrusercontent.com (45.77.52.30): icmp_seq=2 ttl=50 time=20.5 ms

The IP address is a box hosted at Vultr [6], however its IP address doesn’t match with what I see in the PCAPDroid file. What I do see in the PCAPDroid file is that my phone’s IP address isn’t doing the talking to my intercom, but instead it’s an external device directly talking to my intercom, which would explain the sluggish nature of the Comelit Android app.

Can it speak MQTT?

Initially my guess is that MQTT [7] must be the protocol it speaks on port 64100, but after inspecting some of the finer details in Wireshark (since PCAPDroid allows you to download the dump as a PCAP file and open it in Wireshark), it turns out that is simply not the case. The MQTT server is present in the configuration of the doorbell, but not once does my intercom actually reach out to this server, so in the configuration response above, it’s completely useless.

The NPM comelit-client

Continuing on my search of trying to understand how my intercom works, I find out that Comelit has an NPM client [8]. I try to read the code and in there, I can find only one useful bit of code. Apparently if you open a UDP socket, and call it with INFO it will return you some more hardware information. To write a bit of Rust around it, this is what you can do essentially:

use std::net::UdpSocket;

use std::time::Duration;

const LOCAL_IP: &'static str = "0.0.0.0:7432";

const DOORBELL: &'static str = "192.168.1.9:24199";

fn main() {

let info = "INFO".as_bytes();

let udp_socket = UdpSocket::bind(LOCAL_IP).expect("Boom!");

udp_socket

.set_read_timeout(Some(Duration::from_millis(10)))

.unwrap();

let mut buf = [0; 256];

udp_socket.send_to(&info, &DOORBELL).unwrap();

let receive = udp_socket.recv_from(&mut buf);

println!("{:?}", buf);

}

The buf will print out some bytes, and when converting specific ranges to a string, I’m able to find out more about my intercom like it’s mac address and some other hardware information.

To continue on with port 64100 though:

As you can see above, I called port 24199 and not 64100. I still don’t know what protocol it speaks, and from all the information I’ve gathered thus far it seems like this is a custom protocol and one where I can’t find anything about online. The only logical next step right now is to figure out how the protocol works by hand. First, just to confirm that it accepts both TCP and UDP calls, I do a simple test with netcat:

netcat -v 192.168.1.9 64100

Connection to 192.168.1.9 64100 port [tcp/*] succeeded!

netcat -v -u 192.168.1.9 64100

Connection to 192.168.1.9 64100 port [udp/*] succeeded!

Furthermore, it seems like all the TCP requests (I’ll handle the UDP one’s later in another article), especially the one’s that contain JSON, are all prefixed with 8 bytes. Now, my question is: does it really matter what bytes are being set there? To test this out, I’m making a test request by writing these bytes to a file called test_request:

{"message":"get-configuration","addressbooks":"none","message-type":"request","message-id":2}

The 8 white spaces are intentional. Then I do:

netcat -v 192.168.1.9 64100 < test_request

Which returns a set of 18 non-parseable bytes:

0 6 10 0 0 0 0 0

0 239 1 3 0 2 0 0 0 0 0

It clearly doesn’t return a response, so I’m doing something wrong. It’s probably safe to assume the protocol rejects my request. However, these bytes do tell me something because it looks not too unfamiliar to some of the requests I captured with PCAPdroid.

Going back to Wireshark, I can actually see a similar response, except after the “2” I see two more zero’s and two control bytes. Naturally, I’m actually curious if it matters what these two bytes are set to in all honesty.

After a lot of fiddling and manually setting bits and what not, I figured out the basics of the protocol; the TCP part, at least. To successfully make a call to my intercom we should repeat what the Android app essentially does:

- It opens up one TCP stream.

- It opens a channel starting from a random 2-byte address

- It executes a command over that channel.

To elaborate on each step:

Step 1: Open up a Tcp Stream to the doorbell.

In Rust opening up a TCP Stream is done like such:

use std::env;

use std::fs;

use std::io::prelude::*;

use std::net::TcpStream;

use std::time::Duration;

const TOKEN: &'static str = "TOKEN";

const DOORBELL_IP: &'static str = "192.168.1.9";

const DOORBELL_PORT: u16 = 64100;

fn main() {

let token = env::var(TOKEN).unwrap();

let doorbell = format!("{}:{}",

DOORBELL_IP,

DOORBELL_PORT);

let mut stream = TcpStream::connect(doorbell)

.expect("Doorbell unavailable");

stream.set_read_timeout(Some(Duration::from_millis(5000))).unwrap();

stream.set_write_timeout(Some(Duration::from_millis(5000))).unwrap();

}

Now you’re probably wondering what the TOKEN is, but that’s the ID32 token that I described earlier. You can run this code by doing:

TOKEN=xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx cargo run main

Replace the x’s by the ID32 token.

Step 2: Telling the doorbell you’d like to open a channel:

The bytes to send are the following:

00 06 0f 00 00 00 00 00 <-- A header

cd ab 01 00 07 00 00 00 <-- Magical constant 🪄

55 41 55 54 2f 1a 00 <-- The command + 2 channel bytes

To add to the code above:

use std::env;

use std::fs;

use std::io::prelude::*;

use std::net::TcpStream;

use std::time::Duration;

const TOKEN: &'static str = "TOKEN";

const DOORBELL_IP: &'static str = "192.168.1.9";

const DOORBELL_PORT: u16 = 64100;

fn main() {

let token = env::var(TOKEN).unwrap();

let doorbell = format!("{}:{}",

DOORBELL_IP,

DOORBELL_PORT);

let mut stream = TcpStream::connect(doorbell)

.expect("Doorbell unavailable");

stream.set_read_timeout(Some(Duration::from_millis(5000))).unwrap();

stream.set_write_timeout(Some(Duration::from_millis(5000))).unwrap();

let s = 117;

let pre_aut = make_command("UAUT", s);

let r = tcp_call(&mut stream, &pre_aut);

println!("{:02x?}", r);

}

fn make_command(command: &'static str, control: u8) -> Vec<u8> {

// This is the command prefix I see flying by

// every time

let command_prefix = [

0, 6, 15, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

205, 171, 1, 0, 7, 0, 0, 0

];

// The command is then made and two control bytes are

// added to the end

let b_comm = command.as_bytes();

[&command_prefix, &b_comm[..], &[control, 95, 0][..]].concat()

}

fn tcp_call(stream: &mut TcpStream, bytes: &[u8]) -> Option<[u8; 256]> {

let mut buf = [0; 256];

return match stream.write(bytes) {

Ok(_) => {

match stream.read(&mut buf) {

Ok(_) => Some(buf),

Err(_) => None

}

},

Err(_) => None

}

}

Step 3: Executing the actual command

The command is formatted as JSON as described above and the 8 bytes that are put in front are:

00 06 6d 00 2f 1a 00 00

^ ^ ^ ^

| | | |

| | The same channel bits from the command above

| |

Tells you the length of the response

So the first two bytes are always “00 06”. The next two bytes reveal the length of the response in a very convoluted way. “6d 00” means the stream body is 109 bytes long. However, if the bytes f.e. read “6d 01” it would mean that it is (109 + 255 + 1) = 365 bytes long. The generic formula is:

(byte3 to decimal) + ((byte4 to decimal) * 255) + byte4 to decimal

I’m ignoring this in the example, and to write some ugly hacky code, this essentially should work:

use std::env;

use std::fs;

use std::io::prelude::*;

use std::net::TcpStream;

use std::time::Duration;

const TOKEN: &'static str = "TOKEN";

const DOORBELL_IP: &'static str = "192.168.1.9";

const DOORBELL_PORT: u16 = 64100;

fn main() {

let token = env::var(TOKEN).unwrap();

let doorbell = format!("{}:{}",

DOORBELL_IP,

DOORBELL_PORT);

let mut stream = TcpStream::connect(doorbell)

.expect("Doorbell unavailable");

let s = 117;

stream.set_read_timeout(Some(Duration::from_millis(5000))).unwrap();

stream.set_write_timeout(Some(Duration::from_millis(5000))).unwrap();

let pre_aut = make_command("UAUT", s);

let r = tcp_call(&mut stream, &pre_aut);

println!("{:02x?}", r);

let aut = make_uaut_command(&token, s);

let r = tcp_call(&mut stream, &aut);

match r {

Some(aut_b) => {

println!("{:02x?}", aut_b);

println!("WE'RE IN!");

},

None => println!("SADNESS")

}

}

fn make_command(command: &'static str, control: u8) -> Vec<u8> {

// This is the command prefix I see flying by

// every time

let command_prefix = [

0, 6, 15, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

205, 171, 1, 0, 7, 0, 0, 0

];

// The command is then made and two control bytes are

// added to the end

let b_comm = command.as_bytes();

[&command_prefix, &b_comm[..], &[control, 95, 0][..]].concat()

}

fn make_uaut_command(token: &String, control: u8) -> Vec<u8> {

let command_prefix = [

0, 6, 109, 0, control, 95, 0, 0

];

let raw_com = fs::read_to_string("UAUT.json").unwrap();

let com = raw_com.replace("USER-TOKEN", token);

let b_com = com.as_bytes();

[&command_prefix, &b_com[..]].concat()

}

fn tcp_call(stream: &mut TcpStream, bytes: &[u8]) -> Option<[u8; 256]> {

let mut buf = [0; 256];

return match stream.write(bytes) {

Ok(_) => {

match stream.read(&mut buf) {

Ok(_) => Some(buf),

Err(_) => None

}

},

Err(_) => None

}

}

If everything is okay, you should get a JSON response in return which looks like this (I added line breaks and white spaces for readability):

{

"message":"access",

"message-type":"response",

"message-id":1,

"response-code":200,

"response-string":"Access Granted"

}

Naturally, after this succeeded, I could execute the rest of the JSON formatted TCP requests I captured [9]. Unfortunately, however, none of the JSON type requests are responsible for opening the actual doors. This happens through other requests, which are high-likely related to the following scary four-letter terms: CTPP and CSPB, which I’ll talk about in Part 2.