How to copy a file between devices?

Introduction

Copying a file across devices is painful. You’re on your phone, but you want to access a file that’s on your laptop. How do you do it? What about the other way around? What about copying any file between any of your devices? I asked my dad how he copies a file from his phone to his computer, and he replied with: “through mail attachments, or I use WeTransfer if it’s too big.”. If you had asked me 5 years ago, I would’ve said: “through Dropbox”. Obviously, all fair solutions to this common problem, but I want to make it a little harder. Instead, I’ll be looking for the easiest and laziest way, to copy a file between devices. On top of that, I’ll add a couple of rules:

- I can’t use an account from an existing online service (like Dropbox, Google Drive, WeTransfer, email drafts, etc.).

- It needs to be useable for a non-technical person

- Its flow has to be consistent across platforms

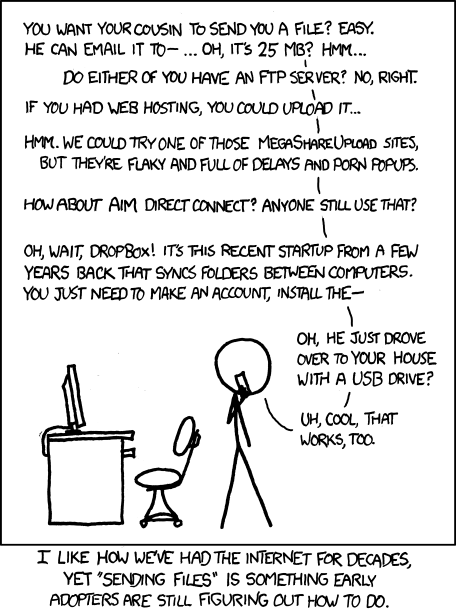

Relevant XKCD:

“Impossible”

Now, you’re looking at the ruleset and think to yourself: “this is impossible”. If I however search online for my predicament - specifically “how do I copy a file from my phone to my laptop” - a Google Support page comes up which reads: “through a USB-cable” [1]. Fair enough, but what about copying it from phone to phone, or laptop to laptop. I can’t use a USB cable in that case; I would have to use an SD-card or a USB-stick.

Another route is Bluetooth, that feature you accidentally turn on from the Android top menu that drains batteries really fast. It might make sense, but the whole pairing feels complex, and unusable for the normal day-to-day user.

If I made an overview of some of the most popular file-sharing technologies out there, and other tools which I’ve used in the past, and test if they match the rules, this would be the list:

| Tool | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dropbox | ❌ | ✓ | ✓ |

| WeTransfer * | ~ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Google Drive | ❌ | ✓ | ✓ |

| iCloud | ❌ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Proton drive | ❌ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Whatsapp ** | ❌ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Mail attachments | ❌ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Terminus [2] | ✓ | ❌ | ❌ |

| scp | ✓ | ❌ | ✓ |

| rsync | ✓ | ❌ | ✓ |

| A USB-cable | ✓ | ✓ | ~ |

| Bluetooth | ✓ | ~ | ✓ |

| Apple’s Airdrop | ✓ | ✓ | ❌ |

* WeTransfer has an anonymous upload function, so it does scratch that itch.

** Whatsapp up until recently had the ability to send messages to yourself. Practically allowing file uploads to yourself. However, for some reason this doesn’t work anymore.

In an ideal world …

… I would’ve been able to open op my phone, tap on a file from the file explorer, and hit share. A device from within my own network would show up, to which I can copy said file. In my personal situation this means: opening up the “Files” app from an Android phone. This “Files” app is actually opening up “Google Files”, and naturally that app wants you to use Google Drive, which breaks rule number 1. Besides, if I start out from my Ubuntu laptop there’s no share button, and no Google Drive.

I could obviously suck it up and install Google Drive, but for this particular use case I don’t want to. Which brings me to the following issue:

No junk in the middle

Another rule I want to add is: “no junk in the middle”. The problem with most file sharing services is that they leave junk behind. Especially the online services like Dropbox, WeTransfer and Google Drive. All of them use storage servers to temporarily or permanently store files. For a use-case which merely revolves around sharing files from one of your devices to another one of your devices, it feels redundant to also have that file stored in the “middle”. Or in other words: leave junk behind.

F.e.: if I were to use Dropbox, the flow would be as such:

- Open up Dropbox (either through a file explorer, or the app).

- Add a file and wait for it to sync.

- Open up Dropbox on the other device and see the file appear.

Let’s take a look at another flow, like using mail attachments:

- Open up a mail provider and sign-in on device 1.

- Create a draft, and add an attachment.

- Open up that same mail provider on device 2, and download the file from the drafts.

Psychologically speaking, a user has successfully achieved its goal after the file arrives at the other device. Cleaning it up afterwards feels like an extra step, and in some cases it is kind of a hard step. In both cases, the file that’s uploaded will either be stuck forever in Dropbox’s folder (or until the user becomes inactive for over quite some time) or it will be stuck in the drafts folder of somebody’s mail service, until they decide to delete it.

Considering that nowadays in The Netherlands huge data parks are required for storing files either permanently or temporarily, which in their turn create all sorts of energy and political problems, I think we do need to take this behavior into account.

If we update the original list above with “4. No junk in the middle”, we get:

| Tool | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dropbox | ❌ | ✓ | ✓ | ❌ |

| WeTransfer | ~ | ✓ | ✓ | ~ |

| Google Drive | ❌ | ✓ | ✓ | ❌ |

| iCloud | ❌ | ✓ | ✓ | ❌ |

| Proton drive | ❌ | ✓ | ✓ | ❌ |

| ❌ | ✓ | ✓ | ? | |

| Mail attachments | ❌ | ✓ | ✓ | ❌ |

| Terminus [2] | ✓ | ❌ | ❌ | ✓ |

| scp | ✓ | ❌ | ✓ | ✓ |

| rsync | ✓ | ❌ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Apple’s Airdrop | ✓ | ✓ | ❌ | ? |

| A USB-cable | ✓ | ✓ | ~ | ✓ |

| Bluetooth | ✓ | ~ | ✓ | ✓ |

For some of these services like WhatsApp or Apple’s Airdrop I’m not sure if there’s a storage provider in the middle. In the case of WeTransfer’s anonymous file transfer, a file persists for seven days. This is not ideal, but it’s slightly better than the alternatives.

A solution

I would like to start out that this merely solves a problem I personally face in my day-to-day life. So, considering the solution needs to be cross-platform the easiest way to get something up and running would be through a web browser.

From the browser there are a couple of things that I can try. Let me say that one of the rules isn’t file size, and neither does it have to be efficient. The dumbest thing I can come up with is the URL itself. A GET-request has an upper limit of 8 kB (or 8192 bytes). This is not a lot, but I could turn a file into a binary-octet stream and read it from the URL. A simple example link would look like such: text file, or in code:

<a download="file.txt" href="data:application/octet-stream;charset=utf-8;base64,Zm9vIGJhcg==">

text file

</a>

All we would have to do here is create a simple HTML page with an upload input, add a file below 7 kB, turn it into a base64 string and copy it over to the receiving end through the URL. On the receiving end, it has to dynamically create a link element, parse the URL and put whatever is in there to the ‘href’ attribute. It’s cross-platform, it’s dumb and easy to use, but the 8 kB is a bit of a restriction. What if my file is bigger than 8 kB?

If I ignore the idiocy of using links to share small files, what this does teach me is that you can turn a file into text, and specifically into a downloadable link. Writing the most minimum of JavaScript, this seems to work as well:

const fileBytes = "foo bar";

const file = new File([fileBytes], { type: "octet/stream" });

const url = window.URL.createObjectURL(file);

const a = document.createElement("a");

a.href = url;

a.download = "file.txt";

a.innerHTML = "text file";

// TODO: add 'a' to the DOM.

All I would have to solve next is a way to send a lot of bytes from one client to the other, without leaving a mess in the middle. A way out could be websockets; it would allow me to stream more than 8 kB of data between clients, but it does require an entire websocket handler. In other words; a server that manages the websocket connections.

Websockets, a love story

Web browsers these days have websocket [3] functionality. For this to work, I’ll need to host a socket handler somewhere within my own network. Each websocket client will be able to connect to the websocket server from their respected devices, and are able to communicate to each other. In other words, send bytes from one to the other. A socket handler in Go looks roughly like this:

package main

import (

static "github.com/gin-contrib/static"

"github.com/gin-gonic/gin"

"gopkg.in/olahol/melody.v1"

)

func main() {

r := gin.Default()

m := melody.New()

r.Use(static.Serve("/", static.LocalFile("./public", true)))

r.GET("/ws", func(c *gin.Context) {

m.HandleRequest(c.Writer, c.Request)

})

m.HandleMessage(func(s *melody.Session, msg []byte) {

m.BroadcastOthers(msg, s)

})

r.Run(":8080")

}

I’m using two frameworks in the example above, Gin and Melody, meaning I’ve officially been cancelled from the Go community. In my defense, I didn’t want to be going through the whole pain of implementing a websocket server from scratch, purely for trying something out. There are tons of other websocket servers out there, but because I’m currently learning Go, this is the one I picked.

The client-side code is where it gets rather complicated, because to make this work a couple of things need to be kept in mind:

- I can’t send a lot of data over the websocket server above, so each file needs to be sliced into pieces.

- The file pieces need to be stitched back together on the receiving end.

Sending files

Sending a file over a websocket is not that complicated if we have to stick to the aforementioned rules. JavaScript has introduced the slice() function to File, and there’s a FileReader() API I can make use of. Firstly, I need to make sure to chunk the file into pieces:

// Assuming there's a multipart input element in the html body:

const chunkSize = 5 * 1024 * 1024;

for (const file of input.files) {

let pointer = 0;

while (pointer < file.size) {

const slice = file.slice(pointer, pointer + chunkSize);

pointer += chunkSize;

}

}

If I have, for example, a file that’s 7 MB, this code will chunk it into slices of 5 MB and 2 MB. The slice method will try to take 5 MB of the end for the 2nd part, but it will read until the end (there’s no need to recalculate the offset).

Secondly, I can read the slice into memory like such:

function readChunk(blob) {

const fr = new FileReader();

fr.readAsArrayBuffer(blob);

fr.addEventListener("load", function() {

const buffer = fr.result;

console.log(Array.from(new Uint8Array(buffer)));

});

}

The reason why I’m converting it into an array is because I’ll be sending it over a websocket later on, and this makes it a bit easier when converting it to JSON, and reading it back.

In the demo below I’m combining both the code snippets from above (feel free to inspect the source).

You can add some files and see the result of the chunking. As you can see, it reads the chunks randomly (unless you added a file that’s below 5 MB).

Receiving files

Receiving files and stitching them back together is a bit strange in JavaScript. As you can see from the demo above, file parts are chunked randomly. Because of this, when stitching the parts back together, you have to retain the order, else the file ends up corrupted on the other side. The next demo is going to look a bit odd, but all this does is echo a file you upload back to yourself, all from within JavaScript.

See it as a really expensive way of doing:

cp file.xyz ~/Downloads

Magical? Isn’t it. Technically, what is happening here is the following: files are being added to a form, they’re chunked and read into memory. Every chunk is being added to a ‘files’ object, and when all the chunks have been read, it reassembles the file back together and turns the file into a URL which can be downloaded by the browser. The full code for the demo looks as follows:

const chunkSize = 5 * 1024 * 1024;

const form = document.getElementById("demo2-form");

const input = document.getElementById("demo2-input");

const result = document.getElementById("demo2-result");

let files = {};

function countParts(parts) {

let partsLen = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < parts.length; i++) {

if (parts[i] === undefined) {

break;

}

partsLen++;

}

return partsLen;

}

function stitchFile(parts) {

let totalLength = 0;

parts.forEach(function (part) {

totalLength += part.length;

});

let totalFile = new Uint8Array(totalLength);

let offset = 0;

parts.forEach(function (part) {

totalFile.set(part, offset);

offset += part.length;

});

return totalFile;

}

function complete(files, name) {

const parts = files[name];

const fileBytes = stitchFile(parts);

const file = new File([fileBytes], { type: "octet/stream" });

const url = window.URL.createObjectURL(file);

const a = document.createElement("a");

a.href = url;

a.download = name;

result.appendChild(a);

a.click();

window.URL.revokeObjectURL(url);

delete files[name];

}

function readChunk(name, blob, part, totalParts) {

const fr = new FileReader();

fr.readAsArrayBuffer(blob);

fr.addEventListener("load", function() {

const buffer = fr.result;

if (!files.hasOwnProperty(name)) {

files[name] = [];

}

files[name][part] = new Uint8Array(buffer);

if (countParts(files[name]) === totalParts) {

complete(files, name);

}

result.innerHTML += "- Part #" + (part + 1) + " of: " +

buffer.byteLength +

" bytes, from file: " +

name +

"\n";

});

}

form.addEventListener("submit", function (e) {

e.preventDefault();

for (const file of input.files) {

let pointer = 0;

let part = 0;

let totalParts = Math.ceil(file.size / chunkSize);

result.innerHTML += "File: " + file.name + "\n";

while (pointer < file.size) {

const slice = file.slice(pointer, pointer + chunkSize);

readChunk(file.name, slice, part, totalParts);

pointer += chunkSize;

part += 1;

}

}

});

Now, all that is left is including some WebSocket functionality to send and receive the bytes. I need to increase the size of the buffers in the websocket server to make sure it can fit 5 MB parts, or stick to the default buffer sizes and instead make tiny 128 kB parts. I’m not sure what the best way is, but I went with the former.

After some tweaking I ended up with a solution that works for me, but how does it exactly hold up if I test it against my own rules? The following table appears:

| Tool | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Custom websocket solution | ✓ | ❌ | ~ | ✓ |

At this point, it is impossible to use for a non-technical person. I can spend quite some time on designing a really nice interface, but the key issue here is that the backend needs to be self-hosted, which are solutions normal users never ever want to think about. I can however think about using a tool like Socketsbay [4] or Postman Websockets [5] to act as the socket server. Likewise, there are probably other paid and non-paid alternatives out there.

Concluding

Copying a file across your own personal devices is still painful. The flow is inconsistent between devices, some tools are available on one device and not the other, and most of them leave junk behind. Web browsers become like cross-platform Swiss army knives, and the file API’s I explored that are available are honestly fascinating. Websockets proved a good enough solution for my own personal pain. However, time-wise it might have been faster to rummage through that one kitchen drawer to find a USB-stick, SD-card or USB-cable.